Serving the worldwide community of radio-electronic homebrewers. Providing blog support to the SolderSmoke podcast: http://soldersmoke.com

Podcasting since 2005! Listen to Latest SolderSmoke

Saturday, January 3, 2026

More on Spark Transmission and Reception -- From Germany. Spark Transmission using a Piezo Fire Starter

Friday, January 2, 2026

Spark Gaps and Coherers demonstrated and Measured by CuriousMarc

Thursday, December 25, 2025

Alexanderson Alternator on 17.2 kHz Copied by YO2DXE in Romania

On December 1st 1924, the 20kW Alexanderson Alternator with the call sign "SAQ" was put into commercial operation with telegram traffic from Sweden to the United States. 101 years later, the transmitter is the only remaining electro-mechanical transmitter from this era and is still in running condition. On Christmas Eve morning, Wednesday December 24th 2025, the transmitter is scheduled* to spread the traditional Christmas message to the whole World, on 17.2 kHz CW.

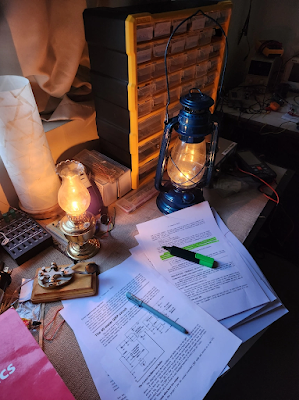

You can listen to the CW from Ciprian's setup above. I listened to it carefully and clearly heard the "KW ALTERNATOR" words at around the 3:30 mark in Ciprian's video. I wondered if this was in fact the SAQ Alternator (but then again, who else would be on 17.2 kHz on Christmas Eve?). I looked at the video from Sweden (below) at around the 49.37 mark we see the operator send "200 KW ALTERNATOR." Through Ciprian's video, I copied "KW ALTERNATOR." So Ciprian's operation was a success. Congratulations Ciprian!

Merry Christmas to all!

Tuesday, December 9, 2025

"Homebrew you say? But did you DESIGN it yourself?"

That is a question we get fairly regularly when we tell the other fellow that our rig is homebrew. I often get the feeling that the question stems from a certain insecurity -- the guy who asks it may feel a bit insecure because the "rig" he is running is completely commercial and his only role in its production was to flash a credit card number.

But lately I have been reading through Jim Williams' wonderful book "Analog Circuit Design -- Art, Science, and Personalities" and I can see that there may be something to this question.

It was the chapter by Barrie Gilbert that made me think more about this. Barrie is the legendary designer for whom the Gilbert Cell is named. This circuit is at the heart of the NE602 chip that many of us used to build our first "Neophyte" receivers and other homebrew rigs. Barrie's chapter is entitled "Where do Little Circuits Come From." Uh oh.

Barrie grew up in the post-war United Kingdom. He father had been killed in a German bombing raid. As a kid, he built crystal radios and, with his brother, "shortwave sets" on softwood bases. He used a TRF receiver that employed Manhattan-style construction. Barrie, it seemed, was one of us.

But then, he suddenly seemed more advanced. He wrote:

"Later, I began to build some receivers of my own but stubbornly refused to use circuits published in the top magazines of the day, Practical Wireless and Wireless World. Whether they worked as well or not they had to be "originals" otherwise, where was the satisfaction? I learned by my mistakes but grew to trust what I acquiered in this way: it was 100% mine, not a replication or mere validation of someone else's inventiveness."

Wow, that is certainly hardcore. I will note, however, that in getting back to the the question about whether I have "designed" the rig myself, I have NEVER had the questioner come back to say that HIS rig was homebrewed from HIS OWN original design. Never. Not once.

And I will note that building a rig from the schematic is an enormous challenge. It is not easy. It is not the mere replication of someone else's inventiveness. Anyone who thinks it is easy should try to homebrew a simple direct conversion receiver. They will discover that it is NOT easy.

I guess this comes down to what we mean by "homebrew." I prefer to stick to the old ham radio meaning of the term: It is homebrew if it was built at home, even if it is built from a schematic done by someone else. When Jean Shepherd built his Heising Modulator, was he working off a schematic from a ham radio magazine? He almost certainly was. But he gathered the parts, laid out the chassis, and put the circuit together. Most importantly, when trouble cropped up, he was able to step in and make the needed corrections. Was his modulator "homebrew?" Of course it was. Did he design it himself? No, his name was not Heising!

More than 100 people built our SolderSmoke Direct Conversion Receiver. We resisted pressure to turn this project into a kit. The folks who built it worked off schematics that we had prepared. They gathered the parts and built their own circuit boards, Manhattan style. They struggled to get the whole thing to work, to make sure the VFO was on the right frequency and at the right level, that the AF amplifier was not oscillating. Were these receivers "homebrew?" Of course they were.

Jim Williams warned that Analog Circuit Design was "A wierd book." He strongly discouraged collaboration between the authors, and noted that this would probably result in "a somewhat discordant book." We see that discord in the hardcore position taken by Barrie Gilbert. Many of the other designers seem to take a more flexible, less austere position. Some even seem to downplay the role of mathematics.

I think Barrie had a right to be proud of his fundamentalism. But not all of us are capable of that. Writing in Jim Williams' book, Samuel Wilensky sums it up nicely:

"I classify analog designers into one of two categories. There are those who do truly original work, and these I consider the artists of our profession. These individuals, as in most fields, are very rare. Then there are the rest of us, who are indeed creative, but do it by building on the present base of knowledge."

Tuesday, December 2, 2025

Grote Reber -- W9GFZ -- Radio Astonomy Pioneer, Homebrew Hero

Second, Grote Reber's mother was also the teacher of Edwin Hubble. Hubble was the guy who discovered that there were OTHER GALAXIES in the universe, and that they were all moving away from each other. That was a BIG discovery! Later, Grote's mom also had her son in her class. Both students were from Wheaton, Illinois.

Lest there be any doubt about Grote's dedication to radio, consider the following. (Much of the following comes from Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grote_Reber)

When he learned of Karl Jansky's work in 1933,[5][6][7] Grote Reber decided this was the field he wanted to work in, and applied to Bell Labs, where Jansky was working.

Pioneer of Radio astronomy

In the summer of 1937, Reber decided to build his own radio telescope in his back yard in Wheaton, Illinois. Reber's radio telescope was considerably more advanced than Jansky's, and consisted of a parabolic sheet metal dish 9 meters in diameter, focusing to a radio receiver 8 meters above the dish. The entire assembly was mounted on a tilting stand, allowing it to be pointed in various directions, though not turned. The telescope was completed in September 1937.[8][9]

Here is a really great article from Sky and Telescope magazine (July 1988) about Reber's homebrew radio telescope:

http://jump.cv.nrao.edu/dbtw-wpd/Textbase/Documents/grncr071988a.pdf

He was limited by the size of locally available 2X4 lumber. Neighbors thought he was trying to control the weather or to bring down enemy aircraft. Between Wheaton and the NRAO site in West Virginia, Reber's telescope spent some time at the National Bureau of Standards site in Sterling, Virginia. I was in Sterling just yesterday. I wonder if there is a plaque or something noting the telesccope's stay in that town. I note that at age 15, Reber had built a ham radio transceiver.

AND THEN HE MOVED TO TASMANIA

He did this because of propagation and low noise conditions. (This reminds me of how we sometimes said that very few people have actually said the words, "And then we moved to the Azores.")

Starting in 1951, he received generous support from the Research Corporation in New York, and moved to Hawaii.[12] In the 1950s, he wanted to return to active studies but much of the field was already filled with very large and expensive instruments. Instead he turned to a field that was being largely ignored, that of medium frequency (hectometre) radio signals in the 0.5–3 MHz range, around the AM broadcast bands. However, signals with frequencies below 30 MHz are reflected by an ionized layer in the Earth's atmosphere called the ionosphere. In 1954, Reber moved to Tasmania,[12] the southernmost state of Australia, where he worked with Bill Ellis at the University of Tasmania.[13] There, on very cold, long, winter nights the ionosphere would, after many hours shielded from the Sun's radiation by the bulk of the Earth, 'quieten' and de-ionize, allowing the longer radio waves into his antenna array. Reber described this as being a "fortuitous situation". Tasmania also offered low levels of man-made radio noise, which permitted reception of the faint signals from outer space.

His Homebrew House in Tasmania

In the 1960s, he had an array of dipoles set up on the sheep grazing property of Dennistoun, about 7.5 km (5 miles) northeast of the town of Bothwell, Tasmania, where he lived in a house of his own design and construction he decided to build after he purchased a job lot of coach bolts at a local auction. He imported 4x8 douglas fir beams directly from a sawmill in Oregon, and then high technology double glazed window panes, also from the US. The bolts held the house together. The window panes formed a north facing passive solar wall, heating mat black painted, dimpled copper sheets, from which the warmed air rose by convection. The interior walls were lined with reflective rippled aluminium foil. The house was so well thermally insulated that the oven in the kitchen was nearly unusable because the heat from it, unable to escape, would raise the temperature of the room to over 50 °C (120 °F). His house was never completely finished. It was meant to have a passive heat storage device, in the form of a thermally insulated pit full of dolerite rocks, underneath, but although his mind was sharp, his body started to fail him in his later years, and he was never able to move the rocks. He was fascinated by mirrors and had at least one in every room.

To Canada -- And a Rejection of the Big Bang

The same July 1988 issue of Sky and Telescope magazine has a good historical vignette of Reber, with a focus on his actvities in Canada late in life (click on the image below). Reber had big doubts about the big bang. Unfortunately this seemed to spill over into scorn and ridicule for those who -- well -- believed in the big bang. We see this at the end of the article. Oh well, even great people sometimes get cranky.

Three cheers for Grote Reber.

Monday, December 1, 2025

Book Review: "Big Ear Two -- Listening for Other-Worlds" by John Kraus (1995)

This book is kind of weird, but give it a chance. The author seems too prone to describe the physical attributes of his colleagues, especially female colleagues. But he was born in 1910 -- he was an old guy when he wrote this book, so perhaps we should cut him some slack. And there is one memorable episode where he defends a female applicant. In spite of the shortcomings, there are many real gems in there, often hidden among the descriptions of 1930's era Kleenex machines and refrigerators. I picked up the book a long time ago and only read it recently.

Here is a good review of Kraus's "Big Ear Two" book:

https://reeve.com/Documents/Book%20Reviews/Reeve_Book%20Review-Big%20Ear%20Two.pdf

Friday, November 14, 2025

Early SSB in India: Espionage, Stolen Secrets, and Kleptomania

Saturday, May 17, 2025

MIT's Haystack Observatory and Dr. Herb Weiss

He spent the bulk of his career developing radar when there was none in the United States. He joined the Radiation Lab at MIT, which was just being established to support the war effort during World War II, designing radars for ships and aircraft. In 1942, when England was in the throes of its air war with the Nazis, Herb went to England and installed radar in planes with a novel navigation system that he and a team had designed for the Royal Air Force. He later spent three years at the Los Alamos, New Mexico, laboratory improving instruments for the A-bomb. After seeing the need for a continental defense network against the Soviet missile threat, he returned to MIT to build it. If not for Herb, there also likely would be no MIT Haystack Observatory, a pioneering radio science and research facility."

Okay. I was born in New Jersey, and my first acquaintance with electronics was about the age of 12 or 13. We had a battery-operated radio, which didn't work, and I asked around about what do we do about it. They referred me to a man two blocks away, who was a radio ham it turned out. So I carried this monster with the big horn and, I guess, the dog sitting on the speaker to his house. We went down in the basement, and I was just fascinated. I was hooked right then and there. A year later I became a radio ham at the age of 13, 14 and literally have been in the field ever since, until I retired. I was fortunate enough to go to MIT as an undergraduate, and most of the people I ran into of that vintage didn't really have a hands-on feeling for electronics. By the time I got to MIT, I had built all kinds of things, including a TV set. Then it turned out that NBC was just trying to get their TV set on the air in New York on top of the Empire State Building."

Phil Erickson

Thursday, April 10, 2025

The History of MOSFETs -- Let us Remember the 40673. The IRF510. And others...

And, of course, about the IRF510.

Monday, February 17, 2025

Direct Conversion Receivers -- Some Amateur Radio History

Tuesday, January 14, 2025

Shock and Awe: The Story of Electricity --- Wonderful Video by Jim Al-Khalili (sent to us by Ashish N6ASD)

Jim talks about the early transatlantic cables, and why some of them didn't work.

We see Jagadish Chandra Bose developing early point-contact semiconductors (because the iron filings of coherers tended to rust in the humid climate of Calcutta!)

There is a video of Oliver Lodge making a speech. There is a flip card video of William Crookes (one of the inventors of the cathode ray tube and the originator of the Crooke's cross).

We see actual coherers.

There is simply too much in this video for me to adequately summarize here. Watch the series. Watch it in chunks if you must. But watch it. It is really great.

Thanks Ashish. And thanks to Jim Al-Khalili.

Sunday, January 12, 2025

Some History of Homebrew Ham Radio -- From Wikipedia and from K0IYE

From Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amateur_radio_homebrew

In the early years of amateur radio, long before factory-built gear was easily available, hams built their own transmitting and receiving equipment, known as homebrewing.[2] In the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, hams handcrafted reasonable-quality vacuum tube-based transmitters and receivers which were often housed in their basements, and it was common for a well-built "homebrew rig" to cover all the high frequency bands (1.8 to 30 MHz). After WWII ended, surplus material (transmitters/receivers, etc.), was readily available, providing previously unavailable material at costs low enough for amateur experimental use.[3]

Homebrewing was often encouraged by amateur radio publications. In 1950, CQ Amateur Radio Magazine announced a ‘‘$1000 Cash Prize ‘Home Brew’ Contest’’ and called independently-built equipment ‘‘the type of gear which has helped to make amateur radio our greatest reservoir of technical proficiency.’’ The magazine tried to steer hams back into building by sponsoring such competitions and by publishing more construction plans, saying that homebrewing imparted a powerful technical mastery to hams. In 1958, a CQ editorial opined that if ham radio lost status as a technical activity, it might also lose the privilege of operating on the public airwaves, saying, ‘‘As our ranks of home constructors thin we also fall to a lower technical level as a group’’.[4]

In the 1950s and 60s, some hams turned to constructing their stations from kits sold by Heathkit, Eico, EF Johnson, Allied Radio's Knight-Kit, World Radio Laboratories and other suppliers.[5]

From "From Crystal Sets to Sideband" by Frank Harris K0IYE https://www.qsl.net/k0iye/

Dear Radio Amateur,

I began writing this book when I realized that my homebuilt station seemed to be almost unique on the air. For me, the education and fun of building radios is one of the best parts of ham radio. It appeared to me that homebrewing was rapidly disappearing, so I wrote articles about it for my local radio club newsletter. My ham friends liked the articles, but they rarely built anything. I realized that most modern hams lack the basic skills and knowledge to build radios usable on the air today. My articles were too brief to help them, but perhaps a detailed guide might help revive homebuilding. I have tried to write the book that I wish had been available when I was a novice operator back in 1957. I knew that rejuvenating homebuilding was probably unrealistic, but I enjoy writing. This project has been satisfying and extremely educational for me. I hope you'll find the book useful...

...My personal definition of “homebuilding” is that I build my own equipment starting from simple components that (I hope) I understand. I try not to buy equipment or subassemblies specifically designed for amateur radio. I am proud to be the bane of most of the advertisers in ham radio magazines. I still buy individual electrical components, of course. I just pretend that the electronics industry never got around to inventing radio communications.

An irony of our hobby is that, when the few remaining homebrewers retire from their day jobs, they often build and sell ham radio equipment. These industrious guys manufacture and sell every imaginable ham gizmo. I doubt any of them have noticed that, by making everything readily available, they have discouraged homebuilding.

Tuesday, October 8, 2024

The Transistor that Changed the World -- the MOSFET

Saturday, September 7, 2024

Sony and the Transistor

I found the comment about Sony's belief that NPN transistors are superior to PNP very interesting.

Tuesday, August 20, 2024

"The Far Sound" -- Bell System Video from 1961 -- Good Radio History (video)

Saturday, May 11, 2024

Jens OZ1GEO's AMAZING Radio Museum

Thursday, March 7, 2024

The Wizard of Schenectady -- Charles Proteus Steinmetz

Such a beautiful article. Ramakrishnan VU2JXN sent it to me. It reminded me of how puzzeled we were when we found "Schenectady" on old shortwave receiver dials, amidst truly exotic locations. Rangoon! Peking! Cape Town! Schenectady? Obviously this was due to General Electric's location in that New York State city. But reading this article, I am thinking that the presence of Charles Proteus Steinmetz had something to do with it. His informal title (The Wizard of Schenectady) confirmed that we have been right in awarding similar titles to impressive homebrewers.

Here is the Smithsonian article that Ramakrishnan sent.

And here is a link to a PBS video on Steinmetz:

https://www.pbs.org/video/wmht-specials-divine-discontent-charles-proteus-steinmetz/

Here is a SolderSmoke blog post about "Radio Schenectady":

https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2020/07/radio-schenectady.html

Wednesday, March 6, 2024

N6ASD Builds a Zinc-Oxide Negative Resistance Transmitter (and a Spark/Coherer rig)

My journey into the world of amateur radio began in a very primitive way. My first "rig" comprised of a spark-gap transmitter and a coherer based receiver. A coherer is a primitive radio signal detector that consists of iron filings placed between two electrodes. It was popular in the early days of wireless telegraphy.

Spark transmitter (using a car's ignition coil to generate high-voltage sparks):

Coherer based receiver (using a doorbell for the "decoherer" mechanism):

When I keyed the transmitter, a high voltage arc would appear at the spark-gap and this produced (noisy) radio waves. The signal would be received by the iron-filings coherer on the other side of the room. A coherer is (usually) a one-shot receiver. You have to physically hit it to shake the filings and bring the detector back to its original state. That's what the doorbell hammer did. It would hit the coherer every time it received a signal. It amazed me to no end. A spark created in one room of my house could make the hammer move in another room. Magic!

Soon after this project, I started experimenting with *slightly more refined* crystal detectors and crystal radio circuits. As most of you would know, these amazing radios don't require any batteries and work by harnessing energy from radio waves. I guess these simple experiments instilled a sense of awe and wonder regarding electromagnetic waves, and eventually, this brought me into the world of amateur radio in 2015.

My main HF rig is an old ICOM IC-735. The only modification on this is radio is that it uses LED backlights (instead of bulbs):

With space at a premium in San Francisco, the antenna that I have settled for is an inverted vee installed in my backyard (and it just barely fits). I made the mast by lashing together wooden planks. For this city dweller, it works FB:

I have recently gotten into CW, and it has definitely become my mode of choice.

I'm a self-taught electronics enthusiast and I love homebrewing radio circuits. I'll be sharing more info about them soon.

Thanks for checking out my page. I hope to meet you on the air!

73,

N6ASD