Serving the worldwide community of radio-electronic homebrewers. Providing blog support to the SolderSmoke podcast: http://soldersmoke.com

Podcasting since 2005! Listen to Latest SolderSmoke

Thursday, December 4, 2025

Jim Williams -- Analog Man -- Book Review: "Analog Circuit Design -- Art, Science, and Personalities"

Saturday, November 1, 2025

Another GREAT Book -- L.B. Cebik, W4RNL's "Seven Steps to Designing your Own Ham Equipment" - 1979 - FREE!

Thanks to Walter KA4KXX for alerting us to this gem of a book. L.B. Cebik is best known as an antenna guru. I did not know that he also did a book on the homebrewing of rigs.

Here is the URL: https://archive.org/details/sevenstepstodesi0000cebi/page/n2/mode/1up Just click on the "borrow" box and you can look at the whole thing. Thanks too to the Internet Archive for preserving this important piece of ham literature.

I was a bit apprehensive when I saw "designing" in the title. We have talked about how, all too often, modern hams seem to challenge the homebrew nature of our rigs by asking if we had "designed" it ourself. "Well," I answer, "I did not invent the Colpitts oscillator, nor the common emitter amplifier, nor the superheterodyne receiver... But I did build this rig myself." I worried that OM Cebik might have been plunging us into this design debate way back in 1979.

But no need for worry. His definition of "design" is quite expansive:

Thanks again Walter.

Thursday, October 30, 2025

"Troubleshooting Analog Circuits" by Bob Pease

Get this book: https://www.amazon.com/Troubleshooting-Analog-Circuits-Design-Engineers/dp/0750694998

Tuesday, October 14, 2025

Radio Shack, Mixers, Terman

Wednesday, May 21, 2025

Grayson Evans KJ7UM Interview at Four Days in May at the Dayton Hamvention 2025

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

On the importance of taking a break.

Thomas K4SWL has a good post about the importance of taking a break from radio. Following up on this, I noted that "taking a break" is often a good way of finding a solution to a difficult problem. I noted that I have confirmed this -- it has worked for me. Pete Juliano N6QW recently announced that he is taking a break from the MHST project. That is a good idea. A solution will likely emerge.

I noted that there is some evidence backing up our suspicion about the benefits of breaks. I earlier shared some comments from Harry Cliff's excellent book, "How to make an Apple Pie from Scratch."

https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2024/04/cloud-chamber-finale.html

Harry also wrote about the usefullness of taking breaks. In 1917 Ernest Rutherford was having trouble understanding the presence of some hydrogen nuclei. Harry writes:

"Again, he was forced to put his work on hiatus to go on a mission to the United States in the summer of 1917, but it turned out to be one of those useful breaks when stepping away from a problem lets your mind slowly work out the problem in the background. When Rutherford got back to the lab in September he had the answer..."

There are many other examples.

So, if you get stuck, take a break!

Monday, September 16, 2024

"QRP Classics" The Book that Got Me Started in Homebrew

A question this morning from Scott KQ4AOP caused me to Google this old book On page 59 I found the article about my first transmitter. Someone has put a copy of the entire book on the interenet. Here it is:

Monday, February 5, 2024

"The Soul of a New Machine" -- Re-reading the Classic Book by Tracy Kidder

This book is especially important to the SolderSmoke community because its title has led to one of the most important concepts in our community and our lexicon: That we put "soul" in our new machines when we build them ourselves, when we make use of parts or circuits given to us by friends, or when we make use of parts (often older parts) in new applications. All of these things (and more) can be seen as adding "soul" to our new machines. With this in mind I pulled my copy of Tracy Kidder's book off my shelf and gave it a second read. Here are my notes:

-- On reading this book a second time, I found it kind of disappointing. This time, the protagonist Tom West does not seem like a great person nor a great leader. He seems to sit in his office, brood a lot, and be quite rude and cold to his subordinate engineers. Also, the book deals with a lot of the ordinary stupid minutia of organizational life: budgets, inter-office rivalry, office supplies, broken air conditioners. This all seemed interesting when I read this as a youngster. But having had bosses like West, and having lived through the boring minutia of organizational life, on re-reading the book I didn't find it interesting or uplifting.

-- The young engineers in the book seem to be easily manipulated by the company: They are cajoled into "signing up" for a dubious project, and to work long (unpaid) hours on a project that the company could cancel at any moment. They weren't promised stock options or raises; they were told that their reward might be the opportunity to do it all again. Oh joy. This may explain why West and Data General decided to hire new engineers straight our of college: only inexperienced youngsters would be foolish enough to do this. At one point someone finds the pay stub of a technician. The techs got paid overtime (the engineers did not), so the techs were making more money than the engineers (the company hid this fact from the engineers). The young engineer who quit probably made the right move.

-- The engineers use the word "kludge" a lot. Kidder picks up this term. (I'm guessing with the computer-land pronunciation that sounds like stooge.) They didn't want to build a kludge. There is one quote from West's office wall that I agree with: "Not everything worth doing is worth doing well." In other words, don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Sometimes a kludge will do.

-- Ham radio is mentioned. One of Wests lead subordinates was a ham as a kid. Kidder correctly connects this to the man having had a lonely childhood. Heathkit is also mentioned once, sarcastically.

-- The goal itself seems to be unworthy of all the effort: They are striving to build a 32 bit computer. But 32 bit machines were already on the market. The "New Machine" wasn't really new.

-- Kidder does an admirable job in describing the innards of the computer, but even as early as the 1978 models, I see these machines as being beyond human understanding. The book notes that there is only one engineer on the hardware team who has a grasp of all of the hardware. The software was probably even more inscrutable.

-- I found one thing that seemed to be a foreshadowing of the uBITX. The micro code team on this project maintained a log book of their instructions. They called it the UINSTR. The Micro Instruction Set. Kidder or the Microkids should have used a lower-case u.

-- The troubleshooting stories are interesting. But imagine the difficulties of putting the de-bugging effort in the hands of new college graduates with very little experience. I guess you can learn logic design in school, but troubleshooting and de-bugging seem to require real-world experience. We see this when they find a bug that turns out to be the result of a loose extender card -- a visiting VP jiggled the extender and the bug disappeared.

-- Kidder provides some insightful comments about engineers. For example: "Engineering is not necessarily a drab, drab world, but you do often sense that engineering teams aspire to a drab uniformity." I think we often see this in technical writing. Kidder also talks about the engineer's view of the world: He sees it as being very "binary," with only right or wrong answers to any technical question. He says that engineers seem to believe that any disagreement on technical issues can be resolved by simply finding the correct answer. Once that is found, the previously disagreeing engineers seem to think they should be able to proceed "with no enmity." Of course, in the real world things are not quite so binary.

-- This book won the Pulitzer prize, and there is no doubt about Kidder being a truly great writer, but in retrospect I don't think this is his best book. This may be due to weaknesses and shortcomings of the protagonist. I think that affects the whole book. In later books Kidder's protagonists are much better people, and the books are much better as a result: for example, Dr. Paul Farmer in Kidder's book Mountains Beyond Mountains.

-- Most of us read this book when we were younger. It is worth looking at again, just to see how much your attitudes change with time. It is important to remember that Tracy Kidder wrote this book when he was young -- I wonder how he would see the Data General project now.

-----------------------

Here is a book review from the New York Times in 1981:

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/99/01/03/specials/kidder-soul.html?CachedAug

Here's one about a fellow who also re-read the book and who provides a lot of good links:

https://auxiliarymemory.com/2017/01/06/rereading-the-soul-of-a-new-machine-by-tracy-kidder/

Saturday, January 20, 2024

K0IYE's Thoughts on Homebrewing and Workshops

I like Frank Harris K0IYE's book so much that I don't mind posting about it frequently. "From Crystal Sets to Sideband" is must-read material for all homebrewers.

The picture above is especially significant. I first came across it in the old pulp-style magazine called World Radio. The picture, like Frank's book, is truly inspiring.

This week I stumbled across a relatively new chapter in Frank's book. Chapter 3A deals with his approach to homebrewing (Luddite, analog, HDR) and his advice on how to set up a home ham-radio workshop. There is a lot of wisdom in this chapter.

The opening paragraph of Chapter 3A really grabbed me. Check it out here. Click on the text below for a better view:

Sunday, December 17, 2023

Make Your Own SDR Software! And, "Analog Man" by Joe Walsh of the Eagles (WB6ACU)

Friday, November 24, 2023

A FREE Book from the Early Days of Ham Projects with Transistors: The CK722 -- The Device that Got Pete Juliano Started in Homebrew

You can get the book for free here:

We are really lucky to have Pete Juliano sharing his vast tribal knowledge with us.

Friday, November 10, 2023

SolderSmoke Podcast #249 -- Travel, Pete's 6BA6 rig, Books!, VFOs, SDR, Computers, Spectrum Analysers, Transistor Man! MAILBAG

Bill's DXCC-100. DONE.

Tribal Wisdom: W1REX on HRWB https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/11/listen-to-rex-w1rex-lots-of-tribal.html

Pete's Bench:

Pete's 6BA6 rig

Pete Re-invents the Shirt-pocket SSB Rig

BEZOS BUCKS ARE BACK! PLEASE BUY THERE! >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

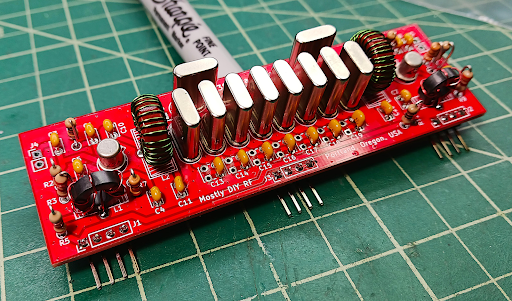

Mostly DIY RF: Work proceeds in the Oregon Silicon Forest on P3ST kit development. Todd is confident the P3ST will be released on December 18th.Many other kits available now: https://mostlydiyrf.com/

Sign up for the newsletter: https://mostlydiyrf.com/subscribe/

Rebuild of the 15-10 VFO (for improved Dial Spread) (with yet another QF-1 capacitor) https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/10/dial-scale-linearity-spreading-out.html

Why Building for 10 meters is harder: https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/09/why-building-for-10-meters-is-harder.html

Copper Tape shielding of 15-10 rig.

Crushing Spurs with Better Bandpass Filters (see blog post) https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/09/crushing-17-and-12-meter-spurs-with.html

Another 15-10 rig in the works... for SSSS. Boards are accumulating...

More problems discovered with the Herring Aid 5 Receiver . Lots of SS blog posts Comment from Rick WD5L. ) https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/10/a-big-error-discovered-in-1976-qst.html Did you try to build one? Did you succeed or did you fail? Please let us know.

The Basil Mahon books (blog posts) https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/11/basil-mahon-is-author-for-us-he.html

The Sunburst and Luminary book of Don Eyles (blog posts)

The Art of Electronics by Horowitz and Hill (blog posts)

Spectrum Analysers: Tiny SA Ultra https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/09/the-tinysa-ultra-spectrum-analyser-video.html and Polarad 632C-1; George WB5OYP gave me one of these spectrum analysers (I NEED a manual! Does anyone have a manual or a schematic? ) :

Stabilizing the EB63A (with Pete recommended LP filters from e-Bay.

MAILBAG:

TRANSISTOR MAN T-SHIRTS! Thanks to Roy WN3F!

Todd VE7BPO on AF amplifiers. Thanks Todd.

Wes W7ZOI -- Always a privilege to exchange e-mail with Wes.

E-mail from Jay Rusgrove W1VD. About the Herring Aid 5.

E-mail from Eamon Skelton EI9GQ! Amazing!

HB2HB with Denny VU2DGR https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/09/hb2hb-contact-with-denny-vu2dgr.html

Nick M0NTV on diode matching for ring mixers: https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/10/does-matching-matter-diode-matching-for.html

Paul Taylor VK3HN on the new Elecraft CW rig.

Dean KK4DAS fixed the noise in his Hallicrafters SW receiver. A long battle, finally won.

Dean also in contact with G3UUR.

Ramakrishnan VU2JXN helping me set up a backup of blog on WordPress.

Mark KA9OOI noticed that SS podcast archive appears gone. In fact just temporarily relocated to http://soldersmoke.com/

(SS PODCAST Archive temporarily relocated to http://soldersmoke.com/

Andreas DL1AJG - Crystal radio video. https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/10/building-crystal-set-videos.html

George N2APB on the Herring Aid 5

Grayson KJ7UM experimenting with Varactors and Thermatrons!

Thomas K4SWL on Mattia's DC receiver. https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2023/10/mattia-zamanas-amazing-direct.html

Bob Weaver of Dial Bandspread Linearity fame. Electron Bunker

Mike Bryce WB8VGE QRP Hall of famer -- he too couldn't get the Herring Aid 5 working.

Kirk NT0Z wrote about the Wayback machine. But this former ARRL staffer he also tried and failed to get the Herring Aid 5 going. Way back when... https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2015/03/kirks-herring-aid-tuna-tin-and-regen.html

Wednesday, November 1, 2023

Basil Mahon is an Author for Us -- He explains Faraday, Maxwell, and Heaviside

PERSONAL:

Born May 26, 1937, in Malta; married Ann Hardwick (a teacher of chemistry), April 1, 1961; children: Tim, Sara, Danny. Education: Attended Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, 1955-57; Royal Military College of Science, B.Sc., 1960; Birkbeck College, London, M.Sc., 1971.

British Army, career officer, serving with Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers in Germany, Aden, and United Kingdom, 1955-74, retiring as major; Government Statistical Office, civil servant, 1974-96. Consultant and trainer on censuses and statistics, including work for clients in Russia, Estonia, Croatia, and Republic of Georgia.

From the Netherlands, Manu Joseph explains why he loves Mahon and Forbes' book on Faraday and Maxwell:

Saturday, October 14, 2023

Paul VK3HN's Video on Scratch-Building and SOTA

Saturday, September 23, 2023

Sunburst and Luminary -- An Apollo Memoir by Don Eyles (video)

Saturday, September 16, 2023

"The Art of Electronics" by Horowitz and Hill (First in a Series of Blog Posts on this Great Book)

Oh man, this book is so good. You really just need to buy it now. I put it in the Amazon link to the right.

OVER HERE >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

The Imsai guy reminded me of this book, and pointed out that earlier editions are more reasonably priced, so I got the second edition (looks like 1980, reprinted many times through 1988). Dean KK4DAS got one too (I think he also got the second edition).

Lest there be any doubt that this book is for us, first let me point to the pictures of Paul Horowitz and Winfield Hill. https://artofelectronics.net/about/

Sunday, April 16, 2023

Inside "Open Circuits"

Monday, March 20, 2023

Winterfest Loot: Who Can ID the Homebrew Receiver?

First a big congratulations to the Vienna Wireless Society and its President, Dean KK4DAS. In spite of low temperatures that made the Winterfest Hamfest live up to its name, this year's 'fest was a big success with excellent turnout both by buyers and sellers. There were a LOT of older rigs -- on one table I saw three HT-37s. It was all great. Here is a video of the hamfest. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oheht5jCuKE&t=619s This was shot early on Sunday morning March 19, 2023, about 30 minutes after it opened. An hour later there were a lot more customers.

Below are pictures of what I found inside. Can anyone tell us what this is? ( I recognized it immediately.) More on this device in due course.

Friday, January 20, 2023

Open Circuits: The Inner Beauty of Electronic Components

I was not going to buy this book. But then, Elisa and I were in a book store and there it was. I decided to take a look. I opened it to a random page: 2N3904. TRGHS. Sold.

It is really interesting.

You can order yours through the Amazon Search block in the right side column of the blog.

Wednesday, December 7, 2022

Is Envelope Detection a Fable? Or is it Real? Diodes, Square Laws and all that

HOW ENVELOPE DETECTION (SUPPOSEDLY?) WORKS

Most of us grew up with the above diagram of how a receiver detects (demodulates) an AM signal. Here is how they say it works:

-- Because of the way the sidebands and the carrier in the transmitted signal interact, we end up with a signal whose "envelope" matches the frequency of modulation. And we just need one side of the envelope.

-- We used a simple diode to rectify the incoming signal.

-- A simple filter gets rid of the RF.

-- We pass the resulting signal through a capacitor and we get audio, which we listen to.

REASONS FOR SCEPTICISM

But recently, a member of my local radio club has questioned this explanation of AM detection. He maintained that "envelope detection" is not real, and that was actually happening was "square law" mixing. I guess there are reasons for skepticism about the envelope detection explanation: The envelope detection explanation does seem very (perhaps overly) simple. This does sound a bit like the kind of "dumbed down" explanation that is sometimes used to explain complex topics (like mixing). Envelope detection does seem consistent with the incorrect insistence from early AMers that "sidebands don't exist." (Of course, they do exist.) All the other detectors we use are really just mixers. We mix a local oscillator the incoming signal to produce audio. Envelope detection (as described in the diagram above) seems oddly different.

Denial of envelope detection can even be found in the ARRL handbook: On page 15.9 of the 2002 edition we find this: "That a diode demodulates an AM signal by allowing its carrier to multiply with its sidebands may jar those long accustomed to seeing diode detection ascribed merely to 'rectification.' But a diode is certainly non-linear. It passes current only in one direction and its output is (within limits) proportional to the square of its input voltage. These non-linearities allow it to multiply."

ISN'T THIS REALLY JUST MIXING, WITH THE CARRIER AS THE LO?

It is, I think, tempting to say -- as the ARRL and my fellow club member do -- that what really happens is that the AM signal's carrier becomes the substitute for the VFO signal in other mixers. Using the non-linearity of the square law portion of the diode's characteristic curve, the sidebands mix with the carrier and -- voila! -- get audio. In this view there is no need for the rectification-based explanation provided above.

But I don't think this "diode as a mixer, not a rectifier" explanation works:

In all of the mixers we work with, the LO (or VFO or PTO) does one of two things:

-- In non-switching mixers it moves the amplifier up and down along the non-linear characteristic curve of the device. This means the operating point of the device is changing as the LO moves through its cycle. A much weaker RF signal then moves through the device, facing a shifting operating point whose shift is set by the LO. This produces the complex repeating periodic wave that contains the sum and difference frequencies.

-- In a switching mixer, the device that passes the RF is turned on and off. This is extreme non-linearity. But here is the key: The device is being turned on and off AT THE FREQUENCY OF THE LO. The LO is turning it on and off. The RF is being chopped up at the rate of the LO. This is what produces the complex repeating wave that contains the sum and difference frequencies.

Neither of these things happen in the diode we are discussing. If you try to look at the diode as a non-switching mixer, well, the operating point would be set not by the carrier serving as the LO but by the envelope consisting of the carrier and the sidebands. And if you try to look at is as a switching mixer you see that the switching is being controlled not by the LO but by the envelope formed by the carrier and the sidebands.

Also, this "diode as a mixer" explanation would require the diode to be non-linear. That is the key requirement for mixing. I suppose you could make a good case for the non-linearity of solid state diodes, but the old vacuum tube diodes were quite linear. The rectifying diode mixer model goes back to vacuum tube days. The "diode as rectifier" model worked then. With tubes operating on the linear portion of the curve, the diodes were not -- could not -- have been working as mixers. We have just substituted solid state diodes for the tubes. The increased non-linearity of the solid state diodes does introduce more distortion, but the "detection by rectification" explanation remains valid.

Even in the "square law" region (see diagram below) an AM signal would not really be mixed in the same way as signals are mixed in a product detector. Even in the square law region, the diode would be responding to the envelope. Indeed, the Amateur Radio Encyclopedia defines "Square Law Detector" as "a form of envelope detector." And even in the square law region, the incoming signal would be rectified. It would be moving above and below zero, and only one side of this waveform would be making it through the diode. Indeed the crystal radio experts discuss "rectification in the square law region" (http://www.crystal-radio.eu/endiodes.htm ) So even in the square law region, this diode is a rectifying envelope detector.

RF Cafe has some good graphs showing the linear and "square law" portions of the crystal diode's curve (see above): http://www.rfcafe.com/references/electrical/ew-radar-handbook/detectors.htm

The crystal radio guys have a good take on square law detection (note, they just see it as rectification, but on a lower, more parabolic portion of the curve): http://www.crystal-radio.eu/endiodes.htm

Here is a good booklet from 1955 on AM Detectors: https://worldradiohistory.com/BOOKSHELF-ARH/Rider-Books/A-M%20Detectors%20-%20Alexander%20Schure.pdf

.jpg)