-- Bill was on Ham Radio Workbench: https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2024/11/bill-n2cqr-appears-as-guest-on-ham.html Our challenge to HRWB. Gauntlet thrown down... OUR CHALLENGE HAS BEEN GRACIOUSLY ACCEPTED! We now extend the challenge to the entire SolderSmoke community: Build one of these: https://hackaday.io/project/190327-high-schoolers-build-a-radio-receiver

Homebrewing is not for the faint of heart! Accept the challenge! Build stuff!

Our question: Did Doug DeMaw ever build an SSB transceiver? Starting in September 1985 he wrote a five part series on an SSB TRANSMITTER for QST. But he prefaces it by asking, "Why would anyone build an SSB transmitter today?" He says it would be fun "for the experience and understanding it would provide." But not for use, you see... And it is not a transceiver.

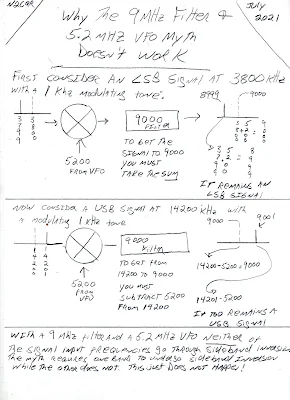

Bill's theory about DeMaw, SSB,CW and sideband inversion: He was a CW guy so sideband inversion did not really matter. He could get it wrong and still make it work.

Pete's Bench:

Brilliance and the TR3. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2C-eYB8yFzg&t=13s

A tale of woe. Done in by a light bulb.

Thanksgiving dinner and SSB transceivers. https://n6qw.blogspot.com/2024/11/11292024-how-to-homebrew-thanksgiving.html https://www.pastapete.com/

Hybrid plans: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKUjHZMf3Fs&t=5s

Dean's Bench:

Travelogue – Falcon 9 Launch

Building a homebrew T Match tuner for the end-fed long wave – sourcing the parts, winding the coil – taps, testing

VWS Makers Projects

SDR Receiver Project – starting in January

VWS Pico Balloon – Traquito - Traquito - WSPR Pico Balloon

Revisiting the 10M DSB rig

Soldersmoke listener challenge – build a DCR with KK4DAS – overview then one board a week

SHAMELESS COMMERCE DIVISION: Mostly DIY RF. Please subscribe to our YouTube Channel. And use the Amazon link on our blog. Become a Patron via Patreon (on the blog). SolderSmoke is now on Blue Sky and Threads -- follow us or at least like us there. Please turn on automatic downloads on your podcast app -- most podcast apps will only store a few episodes. This will help bump the numbers, which will improve visibility. Please give the show five stars and, if possible, a nice review on your podcast service, That will help with the discovery rate for people looking for new podcasts.

Bill's Bench:

Is "The Ground" a Myth? ARRL VP says Ground is a Myth: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KdX-978tvkY. Bill disagrees. Helicopter story. Refrigerator story. Original single wire telegraph system. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-wire_earth_return

Front Panel and Freq Counter for the Mythbuster II.

Another Tale of woe: A mysterious audio problem on the 15-10 II rig. Done in by.... Duh! Comparing sideband suppression with Mythbuster I. Differences in Hfe? Notes on Mythbuster II build.

TinySA Ap -- A cure for Fat Finger Syndrome? : http://athome.kaashoek.com/tinySA/Windows/ How to get and load the Ap (you might want to start watching at 1:11) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zu4X5dyUlpo&t=2s General info video on the TinySA Ultra: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6C24RnYNOWQ&t=1143s

For the DR shack -- I got a Swan SWR-1A on E-Bay.

MAILBAG:

-- Scott KQ4AOP trying to track down the DeMaw SSB transceiver mystery. On the DC Receiver: This was my first receiver build and, it was great fun. When you finish the build and prove you are able to tune through the band, you are welcomed into the secret society! The build is the initiation.I am happy to print and ship the PTO if needed.

-- Bill WA5DSS has built a High School Direct Conversion Receiver!

-- Grayson KJ7UM liked the 1971 video on old THERMATRON AM radios: https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2024/11/basic-radio-circuitry-1971-film.html

-- Chris KD4PBJ sent nice electronic care package.

-- Walter KA4KXX is honored that Dean named his dog for him (Walter was just kidding)

-- Thanks to Bob W8SX for FDIM 2024 interviews.

-- Tony G4WIF insomnia driving him to podcasts. Amazed by quantity of food eaten on Thanksgiving.

-- Nice comment from Trigger about the podcast.

-- Clint says "valves" when he means THERMATRONS. Kindly asks about "Oooo Thats Awesome"

-- Eric 4Z1UG faced with a new challenge. Get well soon OM.

-- Sam WN5C and his Chat GPT AI Elmer.

-- Paul VK3HN on using AI for electronic design. I dunno... Apocalypse Now in the DR?

-- Tommy SA2CLC FB old military gear on QRZ site. Helps with HP8640B repair.

-- Mike WN2A nice comments on Chappy Happy's FB Tezukuri DC RX https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2024/11/tezukuri-and-chappy-happy-amazing.html

-- Allison KB1GMX. Good info on ground truth.

-- Phil W1PJE Had to throw out 15 test leads. Fake wire!

--Todd K7TFC Thoughtful comments on AI and ChatGPT, Help with TinySA Ap

-- Steve KW4H Boatanchor guy. Likes that we often scratch our heads trying to understand.

-- Nick M0NTV built a 40 meter DC receiver: https://soldersmoke.blogspot.com/2024/12/a-40-meter-direct-conversion-receiver.html

-- Dave AA0KU asks about CCI amp (AN762) Also woking on Drakes.

-- Jack (Dhaka Jack!) F4WEF/AI4SV Good thoughts on how to bolster SolderSmoke's ratings.

--Tobias thinks the decline IS ALL HIS FAULT!

-- Tony VE7JUL building a TJ DC RX. Go Canada! Dean says: 3D print PTO former at 110%

-- Jim KI4THC getting his uBITX on the air.

10S November 23, 2024 1517Z SV1AER Kostas in Athens. Said a very sincere “Oh my goodness! Congratulations! That is not a very common thing!” when I told him rig was homebrewed. Nice fellow. Great response.