Like many, I have turned to AI for circuit ideas. And like many, I have been surprised by how many of these ideas just don't work. I have found relatively simple circuits that don't work when built in the real world, and don't work when built in LTSpice. I have already described how AI failed when I asked it a simple question about how many 330 ohm resistors to put in parallel to get 50 ohms. Mike WU2D had found that a lot of AI provided circuits just don't work. (Go to the 10 minute point in his video. )

I was wondering why this is so. So... I asked AI! For those who are sure that their AI is smarter than my AI, let me specify: I just wrote the question into the Google search box and looked at the "AI Overview" in the response.

Here is what AI said:

AI-recommended circuits often fail in the real world due to gaps between simulation and reality, such as a lack of real-world data (noise, rare conditions), AI's inability to grasp complex physical nuances like heat dissipation or component aging, and poor integration with physical prototyping, leading to brittle designs that don't account for manufacturing tolerances or environmental stresses, despite being mathematically sound.

Key Reasons for Failure:

Data Limitations (Garbage-In, Garbage-Out): AI relies heavily on training data; if it's incomplete (missing extreme temperatures, noises, aging effects) or biased, the AI generates designs that work in simulation but not in messy real-world conditions.

- Brittleness & Lack of Context: AI struggles with "edge cases" or novel situations not in its training, leading to fragile designs, much like an AI failing to recognize a rotated bus. It lacks human intuition for subtle physical interactions.

- Physical Nuances Ignored: Simulations often miss crucial real-world physics like heat hotspots from component imperfections, electromagnetic interference, or subtle signal integrity issues, which become critical in physical prototypes.

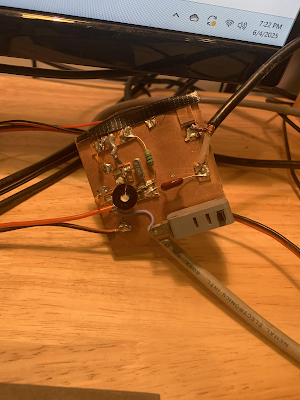

- Manufacturing & Prototyping Gaps: AI designs might be theoretically optimal but impractical to build (e.g., impossible tolerances, complex layouts). The gap between virtual design and physical assembly (poor connections, wrong components) causes failures.

- Validation Challenges: AI-generated circuits need extensive, real-world testing (SPICE simulations, breadboarding, PCB builds) to catch issues, but AI can't perform physical troubleshooting like soldering a damping resistor or witnessing ground bounce in a lab.

- Probabilistic vs. Deterministic: AI works on probabilities, whereas electronics often need deterministic precision. A small error tolerable in some AI tasks can be catastrophic in sensitive circuits.

- Iterative Feedback Loops: Combining AI's speed with human expertise and physical testing to refine designs.

- Hybrid Approaches: Using AI for creative exploration but relying on established physics models (like SPICE) and human judgment for final validation.

- Focus on Integration: Ensuring AI tools work seamlessly with existing engineering workflows and physical constraints.