That is a question we get fairly regularly when we tell the other fellow that our rig is homebrew. I often get the feeling that the question stems from a certain insecurity -- the guy who asks it may feel a bit insecure because the "rig" he is running is completely commercial and his only role in its production was to flash a credit card number.

But lately I have been reading through Jim Williams' wonderful book "Analog Circuit Design -- Art, Science, and Personalities" and I can see that there may be something to this question.

It was the chapter by Barrie Gilbert that made me think more about this. Barrie is the legendary designer for whom the Gilbert Cell is named. This circuit is at the heart of the NE602 chip that many of us used to build our first "Neophyte" receivers and other homebrew rigs. Barrie's chapter is entitled "Where do Little Circuits Come From." Uh oh.

Barrie grew up in the post-war United Kingdom. He father had been killed in a German bombing raid. As a kid, he built crystal radios and, with his brother, "shortwave sets" on softwood bases. He used a TRF receiver that employed Manhattan-style construction. Barrie, it seemed, was one of us.

But then, he suddenly seemed more advanced. He wrote:

"Later, I began to build some receivers of my own but stubbornly refused to use circuits published in the top magazines of the day, Practical Wireless and Wireless World. Whether they worked as well or not they had to be "originals" otherwise, where was the satisfaction? I learned by my mistakes but grew to trust what I acquiered in this way: it was 100% mine, not a replication or mere validation of someone else's inventiveness."

Wow, that is certainly hardcore. I will note, however, that in getting back to the the question about whether I have "designed" the rig myself, I have NEVER had the questioner come back to say that HIS rig was homebrewed from HIS OWN original design. Never. Not once.

And I will note that building a rig from the schematic is an enormous challenge. It is not easy. It is not the mere replication of someone else's inventiveness. Anyone who thinks it is easy should try to homebrew a simple direct conversion receiver. They will discover that it is NOT easy.

I guess this comes down to what we mean by "homebrew." I prefer to stick to the old ham radio meaning of the term: It is homebrew if it was built at home, even if it is built from a schematic done by someone else. When Jean Shepherd built his Heising Modulator, was he working off a schematic from a ham radio magazine? He almost certainly was. But he gathered the parts, laid out the chassis, and put the circuit together. Most importantly, when trouble cropped up, he was able to step in and make the needed corrections. Was his modulator "homebrew?" Of course it was. Did he design it himself? No, his name was not Heising!

More than 100 people built our SolderSmoke Direct Conversion Receiver. We resisted pressure to turn this project into a kit. The folks who built it worked off schematics that we had prepared. They gathered the parts and built their own circuit boards, Manhattan style. They struggled to get the whole thing to work, to make sure the VFO was on the right frequency and at the right level, that the AF amplifier was not oscillating. Were these receivers "homebrew?" Of course they were.

Jim Williams warned that Analog Circuit Design was "A wierd book." He strongly discouraged collaboration between the authors, and noted that this would probably result in "a somewhat discordant book." We see that discord in the hardcore position taken by Barrie Gilbert. Many of the other designers seem to take a more flexible, less austere position. Some even seem to downplay the role of mathematics.

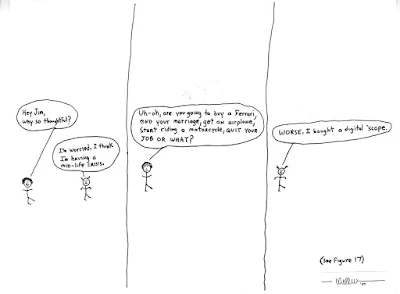

I think Barrie had a right to be proud of his fundamentalism. But not all of us are capable of that. Writing in Jim Williams' book, Samuel Wilensky sums it up nicely:

"I classify analog designers into one of two categories. There are those who do truly original work, and these I consider the artists of our profession. These individuals, as in most fields, are very rare. Then there are the rest of us, who are indeed creative, but do it by building on the present base of knowledge."